The Initiative

VNDLS // Project 001 ft. Faizan Khatri

This page is currently under construction and is accesible only by members

Index

1. Introduction

1.1 Prelude

1.2 Aspiration

1.3 Objectives

2. Methodology

3. Face off

3.1 Initial Imprints

3.2 Observations

4. Research and Analysis

4.1 Kutta Kisko Bola

4.2 References

Books and other resources

4.3 General questions

5. Intervention

5.1 Opportunities and Vision

5.2 Design Direction

6. Design

6.1 Triggers for Design

Material Archive

Identification of location for interventions

Mapping real-time locations for field testing

6.2 Conceptual ideation

6.3 Design Typologies

6.4 Simulations and Technical Specifications

6.5 Prototyping

6.6 Field Testing

6.7 Proof of Concept

7. Story Telling

8. Links to Files

9. Timeline Archives

About Faizan Khatri

The Mentor

The work presented herein has been guided and inspired by Faizan Khatri, who has been intensively involved with Street Animal Research and Design Exploration called The Initiative.

His work includes Studies, mappings, photographic, video-graphic and illustrative documentations knitted over years of understanding and has been featured in this compilation.

Faizan is an architect and educator. He is one of the three partners at studio eight twentythree, a collaborative design practice based in Mumbai, India. The studio's diverse work varies from installation art to spatial design and from visual arts to architecture, achieving a broad perspective of various design streams, through a unique mix of perceptions and influences.

His constant efforts and humble nature have, over the years, inspired several of his students, colleagues and employees to join in his endeavors towards bettering the lives of the street animals.

He has been actively sharing his resources and expertise to guide, design, document and build the Animal Shelter Pods along with a fast-growing team of enthusiastic individuals who believe in this vision through VNDLS.

Faizan would like to extend gratitude to Fatema Master, Sanchita Pawar, Shashank Ahuja, Varun Mehta, Advaita Kelkar, Ami Joshi, Baqer Mehdiyan, Osama Khan, Varun Gulavane, Bharat Sharma, and his partners at the design studio, Samir Raut, Siddhesh Kadam for helping The Initiative take shape.

1. Introduction

1.1 Prelude

We notice them when we want to,

we don’t when we don’t.

“Our concerns for the street animals and our concerns for people are probably related to one another.

The troubles that street animals face are not independent from the troubles that we face (as humans).

It would be easy to see the street animals as a problem and handle them as a problem.

Whereas if we can learn to live together again, maybe we’ll solve our own problems as we try to solve theirs.

That could well be our path towards regaining our fading sense of humor and rekindle our slowly dying joy for life.”

KEDI – documentary film by Ceyda Torun illustrating the lives of street cats in Istanbul, Turkey.

Drawing parallels between the urban humans with street animals like dogs/cats, we observe how they tend to interact (or not) with these co-inhabitants and the way they exist alongside each other.

How does one define a home? Would it be a sprawling built space customized to fancy our luxurious desires? Or would it be a finite volume just enough to accommodate one’s daily existential needs? Or then, would it be a sheet of tarpaulin stretched over a couple of bamboo’s on a neglected pavement, saving one from the onslaught of weather. Or does it simply mean that tiny space below a parked car, or a hole in the compound wall?

Stepping outside the realm of what architecture along with art notionally stands for in its literal sense, The Initiative explores a logical take on the emotional dependence of the urban animals with humans through the lens of what one may call their safe haven ‘my space’.

1.2 Aspiration

There lies immense merit in the argument in today’s time that designers should utilize their skills to resolve societal and environmental problems in the manner of an anti-consumerist approach rather than in support of the capitalist world. From supporting a single user, to a group of users, designers have the ability to create an impact through social design. (Interestingly, social design limits itself to certain sections of society, more so, society implying humans.)

While we share our world with fellow humans as well as animals along with nature, social design in densely populated human areas currently lacks exploration that empathizes with the welfare of street animals. The Initiative aspires to explore bridging that gap, combining art and design towards this endeavor of creating architecture for the non-human component of cities.

1.3 Objectives

The Initiative presents a study and illustration of the lives of stray animals and their habitat in different given cultural and physical conditions in the city of Mumbai. This further culminates into building animal shelter pods and feeders as usable/habitable art installations in different areas by deconstructing a typical street usage in a given city in India and intervening accordingly with the opportunities that present themselves. These pods would then begin to act as a safe haven for animals along with a pause point for humans, facilitating interaction if they desire acting as non-intrusive art inserts for the street dwellers and passers-by alike.

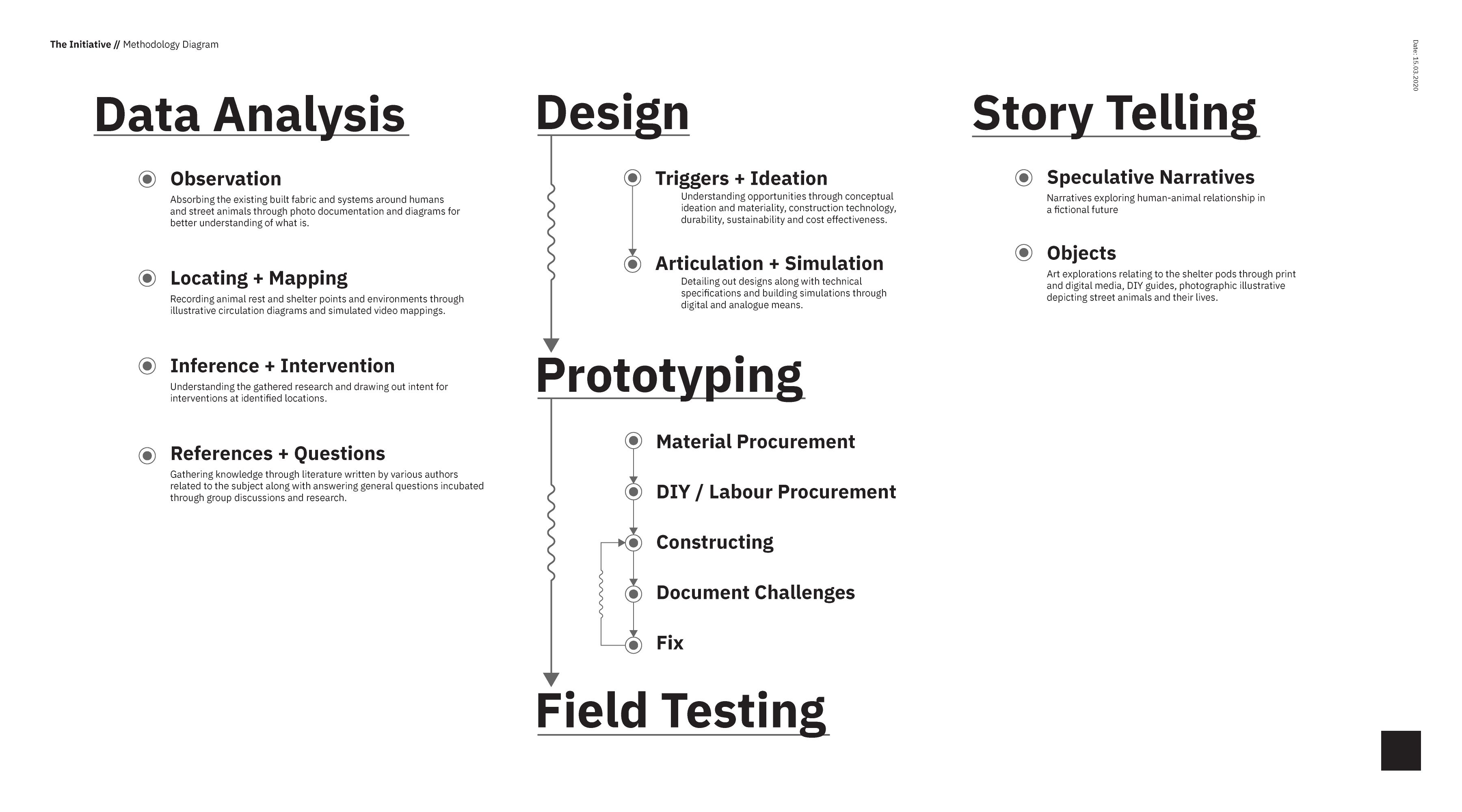

2. Methodology

VNDLS is a group young designers/creative individuals allocating time every Sunday for this project.

We call this the Sunday Service meetings. This is when the group collectively meets holding dialogues towards planning and ideation.

The collaboration has devised a process which mainly involves learning from observation, designing, prototyping and field testing. The group believes in the intimacy involved with creating mock ups and trying them out in actual sizes.

The entire process has been meticulously guided by Faizan Khatri, who has been intensively involved with Animal Research and Design called The Initiative at studio eight twentythree, which houses most cats and dogs from the neighborhood.

The group is also incubates on data collection + analysis, and experiments with story telling in order to guide the designs. Their methodology constantly evolves and expands its horizons organically with each new development that takes form.

3. Face Off

3.1 Initial Imprints

Mumbai city houses (or rather, witnesses) a stray or street dog population of close to one lakh. Out of which the population of street dogs in the Suburban Mumbai district is eight times larger. [1] (There is are no statistics available for the street cat population as of today.) Compare this to the 220 lakh human population of Mumbai, out of which the number of humans populating the slums/streets is close to an astonishing 60%. That’s 132 lakh in numbers. [2]

Interestingly, the street dwellers, humans and animals, share a rather strong interdependence with regards to their psychological well-being and security. These animals are often conferred upon a name and considered as a close family member by those who live with them on streets. They end up forming an inseparable bond, which continues through life and generations. The street animals are found taking shelters under parked vehicle and other unsafe areas in proximity, often running a high risk of meeting with critical physical damage being run over and a lot times with an utterly painful death.

[1] As per survey carried out by the Mumbai Municipal Corporation in Oct 2017. Sources: the Asian Age, the Indian Express

[2] As per survey carried out by the Mumbai Municipal Corporation. Source: the Indian Express

3.2 Observations

It emerges strongly that their existence is easy to be ignored (we assume ‘their’ in this regard to be animals as well as humans that dwell on the streets); Ironically, shutting off their presence from the spectrum of vision for the (remaining) privileged 88 lakh urban dwellers of the city equipped with a shelter above their heads is often the case than not. Here probably lies the germination of the problem, and hence an attempt at a design intervention to address this lacuna.

4. Research + Analysis

4.1 Kutta Kisko Bola

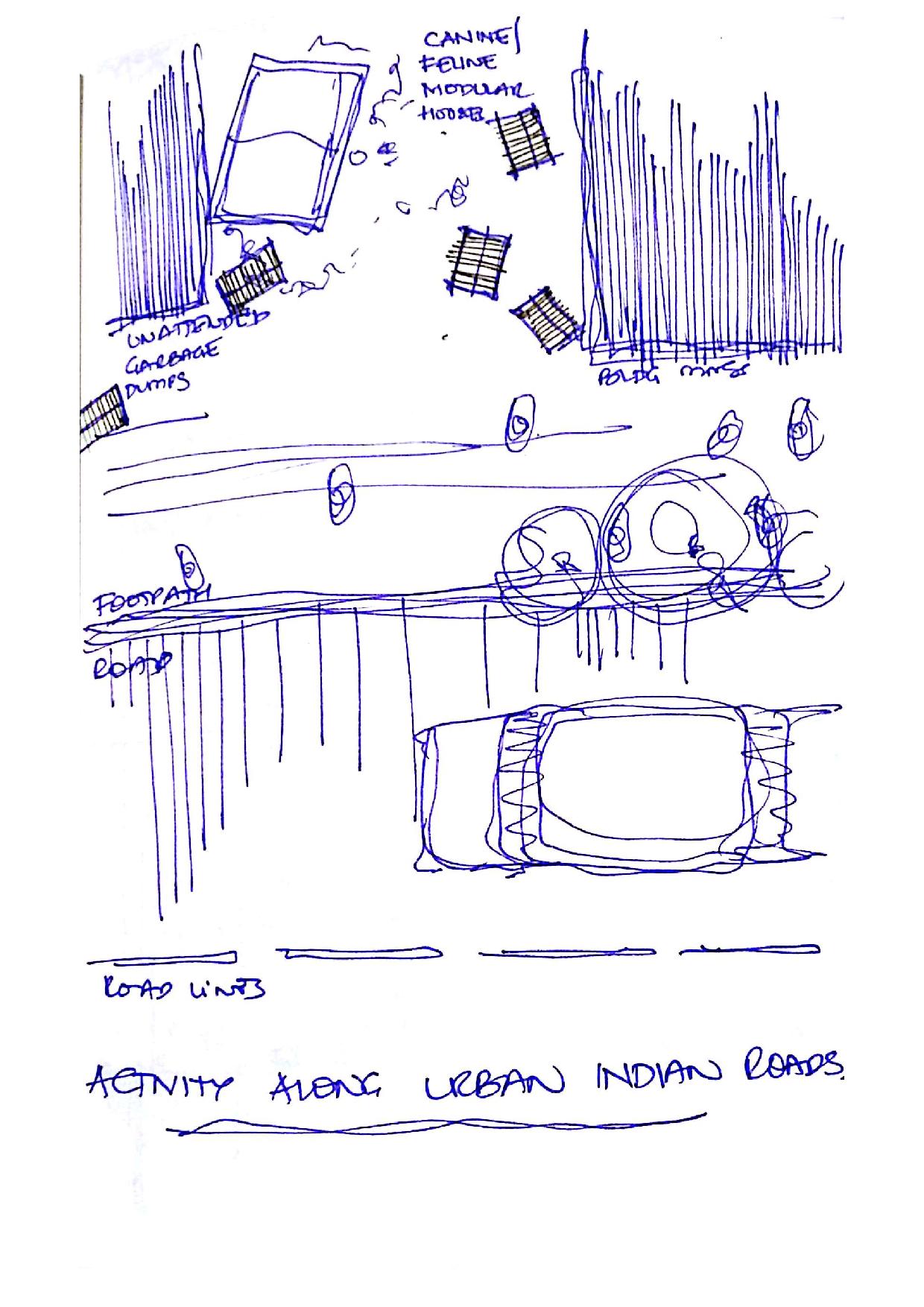

The mapping exercises carried out by Faizan Khatri involved observing the animals through days to understand their movement patterns, pause points, resting points, covered / open to sky at different times of the day/night. The paths and pauses were then articulated through an illustrative circulation diagram helping us understand their interesting lives in the urban environment created by humans.

Dog Name:Jenny

Location: Shivaji Park

Dog Name:Boy

Location: Colaba

Dog Name:Rani/Puppi

Location: Versova

Dog Name:Moti

Location: Nerul

4.4 References

Books and articles

1.

Author:

Rishi Dev

Book Name:

The Ekistics of Animal and Human Conflict // 2014

2.

Author:

Alan Beck

Book Name:

Between Pets and People, the Importance of Animal Companionship // 1983

The Ecology of Stray Dogs: A study of free ranging urban animals // 1973 & 2002

New Perspectives on our Lives with Companion Animals // 1983

3.

Author:

Aysha Akhtar

Book Name:

Animals and Public Health // 2011

Our Symphony with Animals // 2019

4.

Author:

Arnold Arluke

Book Name:

Regarding Animals // 1996

Just a Dog // 2006

Beauty and Beast (postcard book) // 2010

5.

Author:

Clinton Sanders

Book Name:

Between Species // 2009

6.

Author:

Frank Ascione

Book Name:

International Handbook of Animal Abuse and Cruelty // 2008

7.

Author:

Phil Arkow

Book Name:

Animal Cruelty, Antisocial Behaviour and Aggresion // 2012

8.

Author:

Caroline Stevens

Book Name:

Voice s for Animal LIberation // 2020

9.

Author:

Doris Lessing

Book Name:

The old woman and her cat (fiction) // 2013

4.5 General Questions

(1) Why do street animals exist?

Street dogs and feral cats exist in large numbers in developing country like India:

• Human settlements (urban and rural both) inevitably create a noticeable amount of garbage that lies exposed. This essentially enables the street animal’s existence. The animals quickly learn to scavenge. In the absence of this food source, they would have a a tougher time sustaining.

• Couple this with their high reproduction rates and numbers. A female dog gives birth to an approximate of two litters of 4-10 pups each year. Cats have a higher number of three to four litters of up to 3-9 kittens annually. Thus the entire population grows exponentially over years.

• Cities and towns in India have a huge amount of population surviving on the streets (Mumbai has an astonishing 60% of its population living on the streets!). The street dwellers, humans and animals, share a rather strong interdependence with regards to their psychological well-being and security taking care of each other.

• Shopkeepers and others take active interest in tending to the needs of these animals, feeding them and looking out for their health.

(2) Are there laws pertaining to the rights, responsibilties of care-takers and welfare of street animals?

India endorses ahimsa (non-violence) and this has always enabled people to peacefully co-exist with animals. It is a citizen’s duty to show compassion towards all living creatures according to Article 51A(g) of the Constitution. A fundamental freedom guaranteed to the citizens of India, is the freedom to choose the life they wish to live, which includes facets such as living with or without companion animals and moreover assigns a duty to ensure animals are taken care of and respected whist watching out for any kind of cruelty towards them. Resident Welfare Organisations and Apartment owners associations cannot object pets as companions and cannot form laws against it, neither against permissible ways of housing and feeding street animals within society boundaries, even by majority. A “ban” for animals/pets is considered illegal by the law.

Although the AWIB recognises pet owners and care givers to stray animals as different entities, their duties and responsibilities intersect. A pet owner or a stray care giver, should ideally take care of the health, sterilisation, and vaccination of the animal. This can either be done privately or with the help of animal welfare organisations.

Personally, it is the responsibility of the owner or the care giver to maintain cleanliness and hygiene where the animal defecates, lives and feeds.

They also have to make sure that the animals are not a nuisance to others around them.

The Animal Welfare Board of India (AWBI) has listed down in detail, all acts, rules and laws pertaining to the rights of animals and prevention of cruelty on their website. (http://www.awbi.in/policy_acts_rules.html )

(3) Are there any provisions to keep the street animal population under control?

Large populations of stray dogs and cats turn into public health concerns. Dog bites, rabies, leptospirosis, cat scratch fever, and so on are all risks for people living in areas with large populations of strays which often leads to territorial fights and incessant barking at nights. While it’s important to ensure the welfare of street animals, it’s equally important to keep a check on their population to control the spread of diseases and prevent possible bites and attacks.

Animal Welfare Board prescribes Animal Birth Control Rules, 2001 (ABC) as the only effective methodology of keeping the street animal population under check along with vaccinations. The Honorable Supreme Court of India has further ordered the implementation of the ABC program to control the street dog population in all states of India since 2015.

ABC involves spaying of females and castration of male dogs so that they do not reproduce. Vaccination involves giving the dogs an anti- rabies shot. After sterilization the dogs do not reproduce and hence their population becomes stable. As they are vaccinated against Rabies and other diseases they do not pose any health hazard and live out their natural lives healthily and harmlessly, while protecting their territories from other aggressive dogs that may want to enter.

NGOs / individuals take up responsibilty to assist with ABC in their respective areas of functioning via a closed network of communication.

(4) What are the broad categories of differentiation in animal identification as a pet / a street animal?

Definitions are based on two quantifiable parameters: the level of an animal's dependency on humans and the level of its restriction by humans (World Health Organization, 1988).

The first of these refers to the intentional provision of those needs, such as food, shelter and care, necessary for the survival and well-being of the animal. Although it was recognized that this dependency of animals on humans was a gradient ranging from total dependency to none, the following three categories of dependency were proposed:

•Full dependency – the animal is given all of its essential needs intentionally by humans

•Semi-dependency – the animal is given some of its essential needs intentionally by humans

•No dependency – the animal is given none of its essential needs intentionally by humans.

The second parameter, restriction by humans, refers to the control of any contact, association and communication with other animals and people, either through physical restriction (e.g. confinement to premises, leashing) or through direct supervision and control when outside the premises. Again, three categories of restriction are recognized:

•Full restriction – fully restricted or supervised

•Semi-restricted – movements and associations only partially restricted

•No restriction – not subject to any restriction whatsoever.

Four broad categories of animals which exist:

•Restricted animal – fully dependent on their owners and fully restricted or supervised

•Family animals – fully dependent on their owners, but movement and contacts only partially restricted

•Neighborhood animals – partially dependent on the intentional fulfilment of basic needs by humans, but subject to only partial or no restriction

•Feral animals – independent of intentional human provisioning and unrestricted.

5. Intervention

5.1 Opportunities and Vision

With these imprints at hand, we begin to envision design/ art in a uniquely layered city such as Mumbai. This offers an opportunity to dab into the tangible and intangibles while exploring the overlaps between various paradigms like culture, emotions and ‘human’ values.

Locations such as a busy street corner, a dilapidated dysfunctional planter at the edge of the main road, the neglected dead end at a mohallah, the niche in the compound wall of a housing society. These give way to a collapsible pod for temporary fosters on the street or inside a structure for a frail pup or that tiny abandoned kitten amongst many other locations, thus believing in making a difference, a tiny one nevertheless, to those whose lives matter.

5.2 Design Direction

The design intent dabbles between what would be absolute necessities with generous sprinkles of dreams and aspirations. The direction varies from responding to materiality, temporality, efficiency, climate responsiveness, durability, reparability and minimal intrusion to aesthetics, art installation value, high detailing, sustainability, modularity, light weightiness, collapsibility, and cost effectiveness.

6. Design

6.1 Triggers for Design

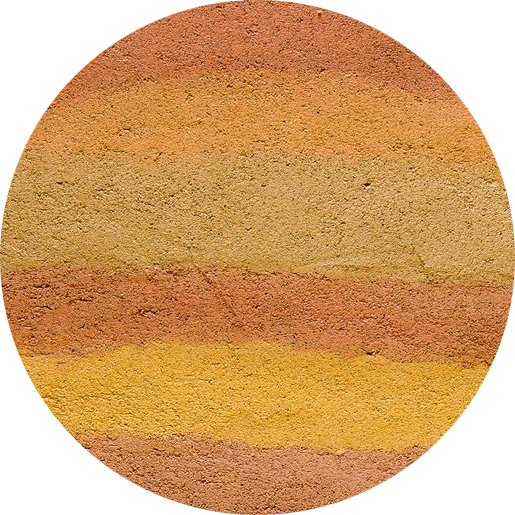

a. Material Archive

Hempcrete

Microconcrete

Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene

Recycled Plastic Modules

Terracotta

Clay

Waste Fabric

Birch Ply

Tyres

PVC Pipes

Rammed Earth

Corrugated Plastic Sheets

b. Identification of Locations for interventions

Mapping places where strays are usually found

•Compound Wall

•Corporate Smoking zones- Ash Trays

•Bus Stops

•Street Furniture: Benches

•Planter Boxes

•Road Dividers

•Gates

•Dustbins

•Tapris

•Gardens

• Street Dwellers

c. Mapping realtime locations for field testing

Shivaji Park

Dadara West

![]()

Dadara West

Skate Park

Carter Road Bandra West

![]()

Carter Road Bandra West

823

Prakash Building Garage, Dadar

![]()

Prakash Building Garage, Dadar

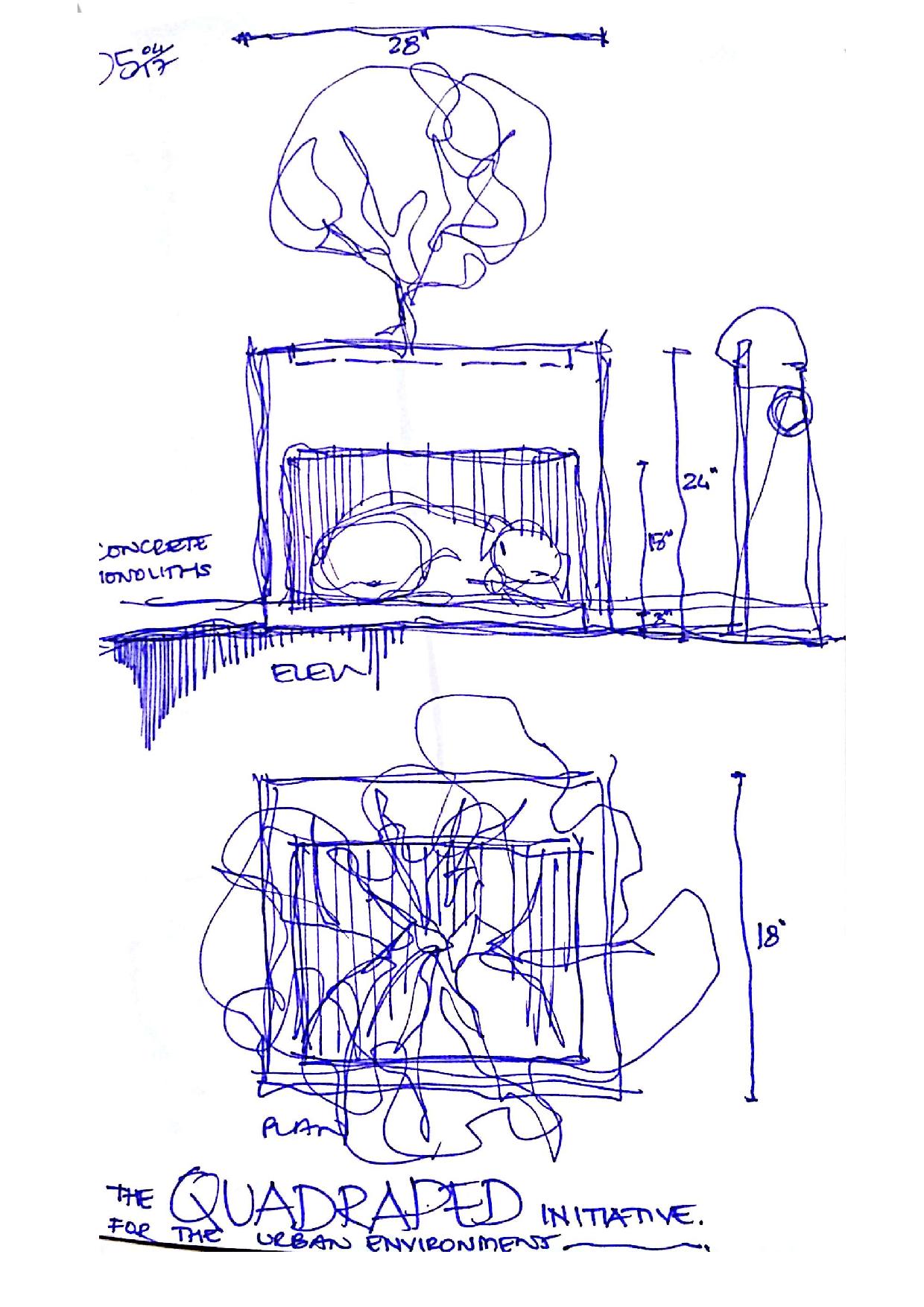

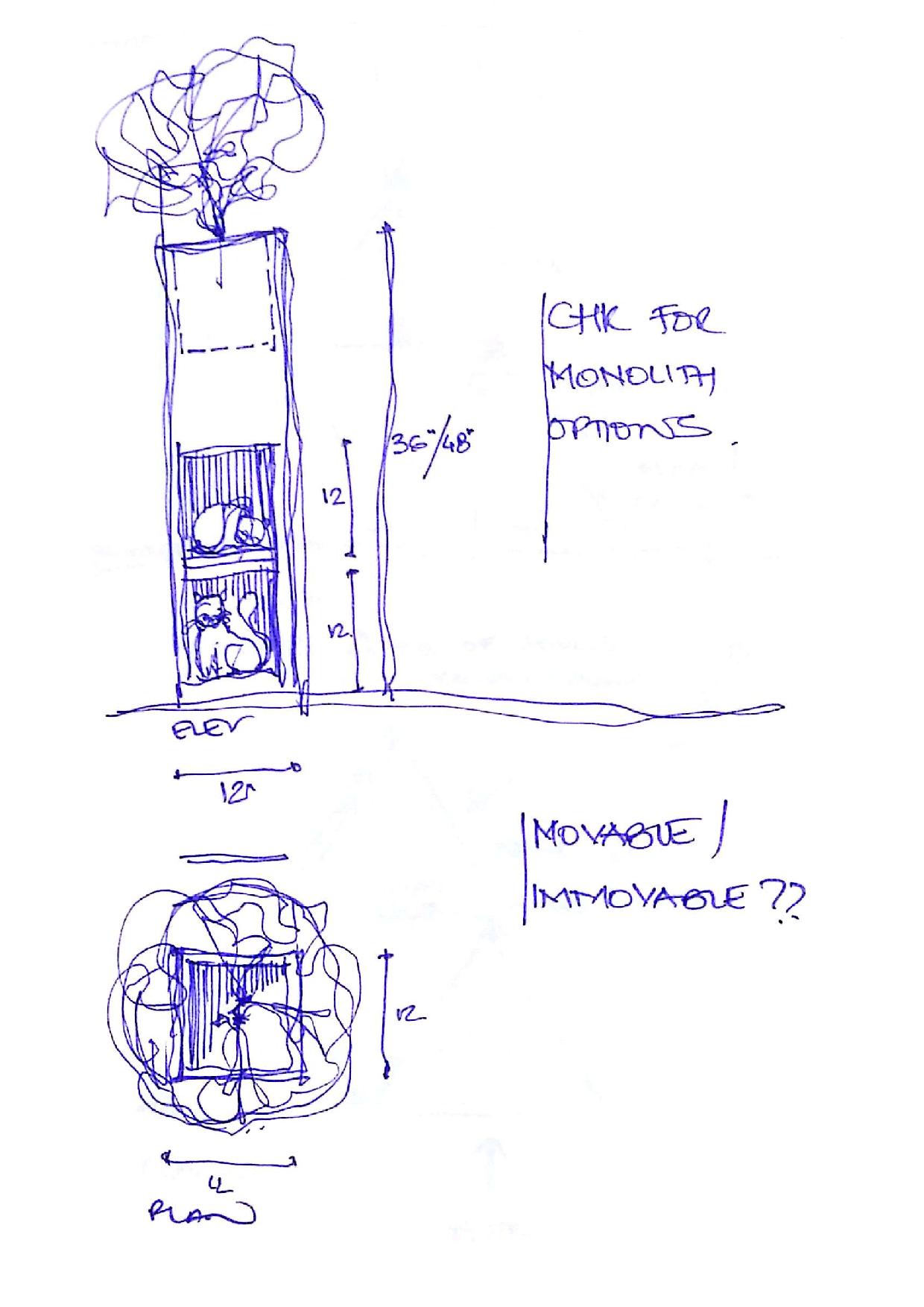

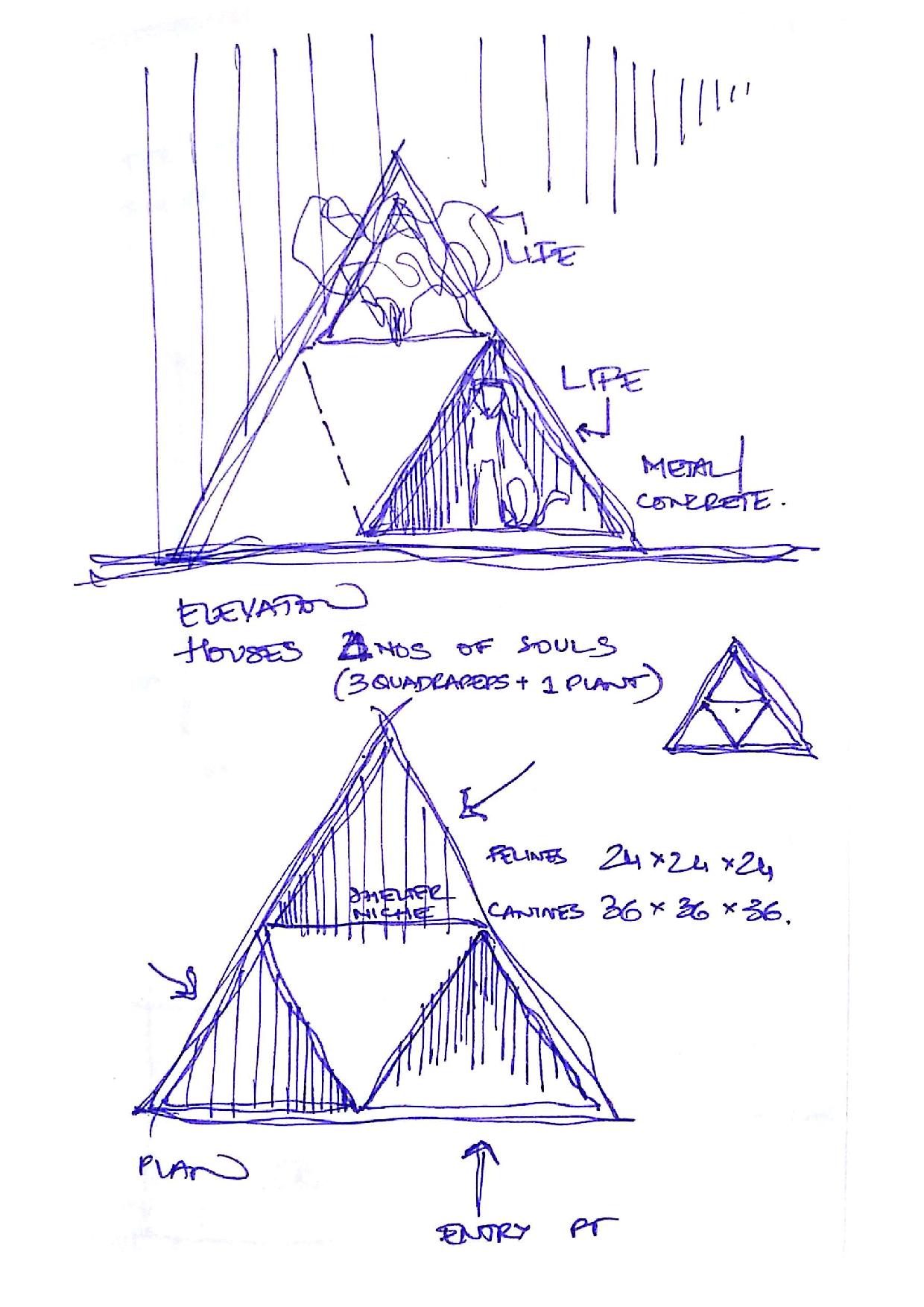

6.2 Conceptual Ideation

6.3 Simulations

6.5 Design Typologies and Technical Specification

WIP 001

001Name: Modular Pod

002

002Name: Bubble Pod

003

003Name: Pyramid

004

004 Name: Billi Bowl

005

005 Name: Tyre

006

006Name: Cube

6.6 Prototyping

6.7 Field Testing

Images on site

8. File Archive

VNDLS_Data Archive

VNDLS_Material Archive

VNDLS_Design Archive

VNDLS_Interview Survey

VNDLS_WriteUp

Billikutta Tales_Google Drive

9. Timeline Archive

15 Dec 2019// Introductions and defining Path

22nd Dec 2019// Taking up tasks and triggering fabrication 05th Jan 2020// Research Structure, Tyre Ideation, Scans First Look, Identity Initiation 12th Jan 2020// Format and story telling discussion 19th Jan 2020// Format Documentation Parameters, AWBI laws, Prototype Model, first draft of story telling 26th Jan 2020 // Casted Billi Bowl, Tyre Material, Finalise format

9th Feb 2020// Taj mahal Tea house, Mini Review 16th Feb 2020// Interview discussion, Format, Design upgrades, Field Days, Funding and crowd funding options 23rd Feb 2020// Finally we review + Google Drive Set up

27th Feb 2020 // Tyre Prototype at Pendses

5th March 2020 // Design Digital Documentation 15th Mar 2020 // Google Drive Organisation, Web Documentation Beta 1.0, Pod Illustrations 26th March 2020 // Google Hangout Call 29th March 2020 // Sharing Speculative futures and the collective dialougue around it 5th April 2020 // Web Documentation Beta 2.0

11th April 2020 // Web narrative review

19th April 2020 // Conference call to assign tasks

1st May 2020 // Web Documentation Beta 3.0

2nd May 2020 // Tasks during the lockdown

6th May 2020 // Web 4.0

20th May 2020 // Meet to organise excels, tech sheets and illustration mock

31st May 2020 // Final Web + Revamp with material archive and text updates 6th June 2020 // Drop down menu Web, Kutta kisko bola

7th June 2020 // Tech Sheets, Crate Designs, Illustrations, The initiative Logo, Material based methodology,